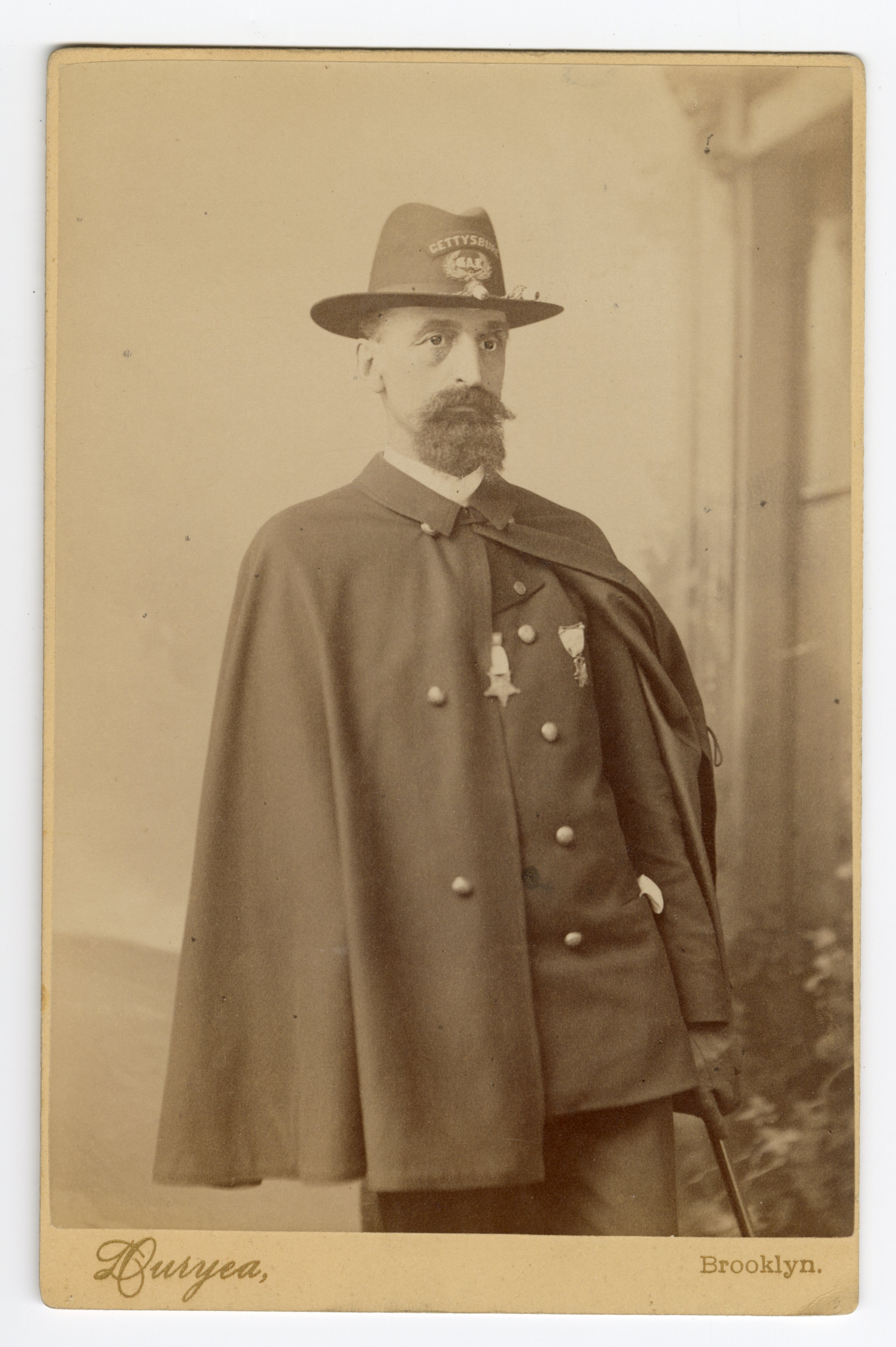

5th Maine Light Artillery - Medal of Honor at Chancellorsville & Wounded at Gettysburg - NEW

Item CDV-11724

John F. Chase

Price: $2000.00

Description

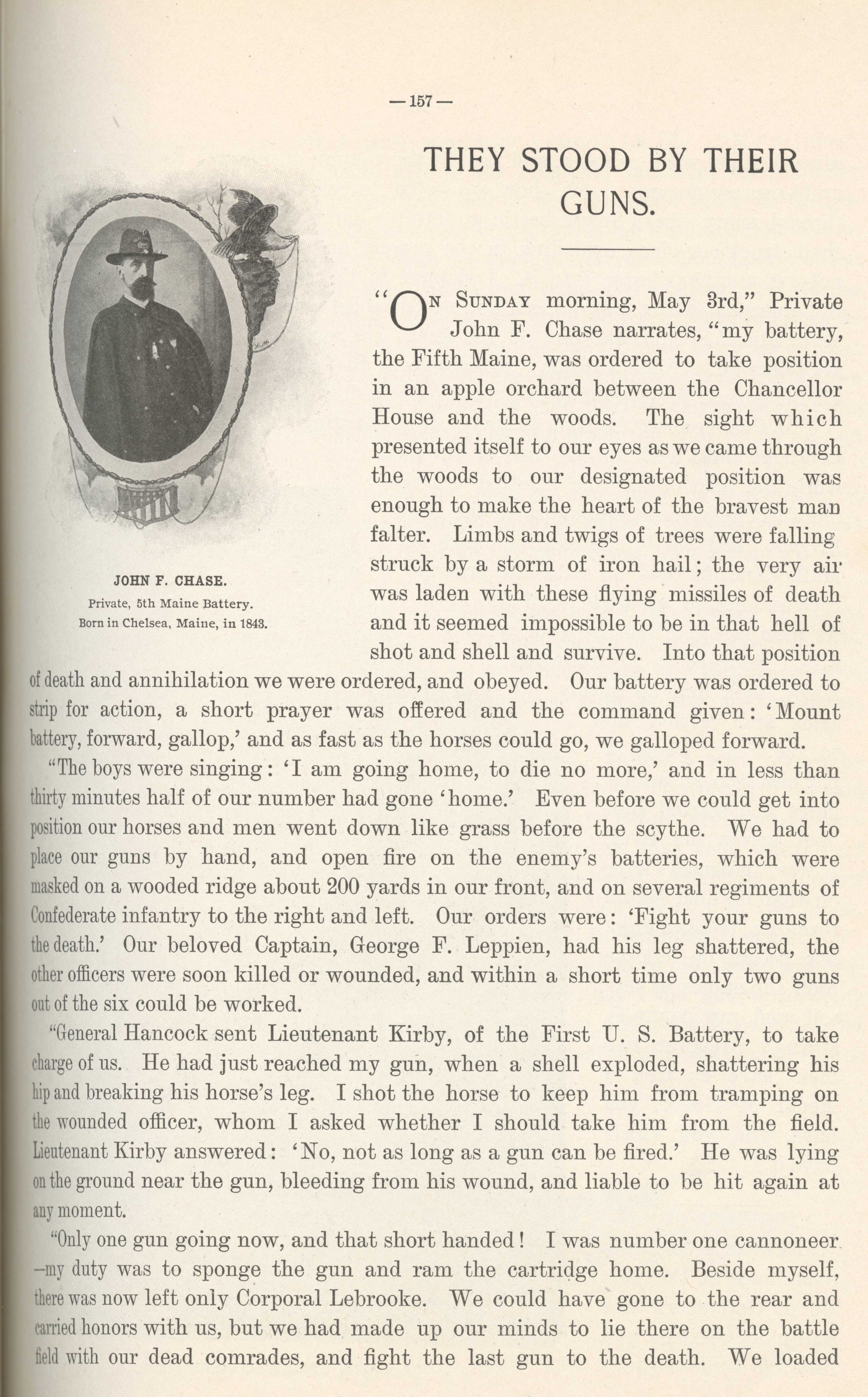

THEY STOOD BY THEIR GUNS."ON SUNDAY morning, May 3rd," Private John F. Chase narrates, "my battery, the Fifth Maine, was ordered to take position in an apple orchard between the Chancellor House and the woods. The sight which presented itself to our eyes as we came through the woods to our designated position was enough to make the heart of the bravest man falter. Limbs and twigs of trees were falling struck by a storm of iron hail; the very air was laden with these flying missiles of death and it seemed impossible to be in that hell of shot and shell and survive.

Into that position shot and shell and survive. Into that position of death and annihilation we were ordered, and obeyed. Our battery was ordered to strip for action, a short prayer was offered and the command given: 'Mount battery, forward, gallop,' and as fast as the horses could go, we galloped forward.

" The boys were singing: 'I am going home, to die no more,' and in less than thirty minutes half of our number had gone 'home.' Even before we could get into position our horses and men went down like grass before the scythe. We had to place our guns by hand, and open fire on the enemy's batteries, which were masked on a wooded ridge about 200 yards in our front, and on several regiments of Confederate infantry to the right and left. Our orders were; 'Fight your guns to the death.' Our beloved Captain, George F. Leppien, had his leg shattered, the other officers were soon killed or wounded, and within a short time only two guns out of the six could be worked.

" General Hancock sent Lieutenant Kirby, of the First U. S. Battery, to take charge of us. He had just reached my gun, when a shell exploded, shattering his hip and breaking his horse's leg. I shot the horse to keep him from tramping on the wounded officer, whom I asked whether I should take him from the field. Lieutenant Kirby answered: 'No, not as long as a gun can be fired.' He was lying on the ground near the gun, bleeding from his wound, and liable to be hit again at any moment.

" Only one gun going now, and that short handed! I was number one cannoneer-my duty was to sponge the gun and ram the cartridge home. Beside myself, there was now left only Corporal Lebrooke. We could have gone to the rear and carried honors with us, but we had made up our minds to lie there on the battle field with our dead comrades, and fight the last gun to the death. We loaded several times with canister, and fired at the column of infantry that was charging up to capture our guns. Oh! how we hated to see the guns that we had served through many a hard fought battle, go into the hands of the enemy. At last a rebel shell struck our piece, exploding in the muzzle, and battering it so that we could not get another charge into it. I stepped to the rear of the gun, and reported to Lieutenant Kirby that our last gun was disabled and only two of us left. I also asked him if I could take him off the field. He replied: 'No, not until the guns are taken off.' What a display of courage in that young officer, lying there with his life's blood slowly ebbing away and putting duty before life.

" At this moment the Irish Brigade came charging in to our support. Corporal Lebrooke and I held up the trail of our gun, while the men of the One hundred and sixteenth Pennsylvania, belonging to the Irish Brigade, and led by Colonel St. Claire A. Mulholland, hitched on with the prolong rope and helped us draw it off the field. As soon as I saw that the guns were safe, I returned to Lieutenant Kirby, took him up in arms and carried him to the rear, where I put him into an ambulance and started him back across the river. I was informed later on that he died before reaching Washington, but before he left, he took the names of myself and my comrade, saying: 'If ever two men have earned a Medal of Honor, you have, and you shall have it."

PRIVATE CHASE's experience at the battle of Gettysburg was still more exciting and resulted disastrously for the heroic soldier, who at that battle was made a cripple for life.

" My battery," he says, "took position on the north side of the Seminary buildings on Seminary Hill, where we fought from 10 o'clock until four on the first day's battle at Gettysburg, July 1st, losing nearly two-thirds of our corps, and being outnumbered five to one. We were forced to fall back through the town of Gettysburg and take position on a knoll between Cemetery and Culps Hills, which position the battery held during the second and third days' battles. It was the time of the historic charges of Early's Division, led by the Louisiana 'Tigers,' on the Union batteries on East Cemetery Hill. My battery was enfilading the charging column as it dashed up the hill. Our shot, shrapnel, and canister was doing such terrible execution that the Confederates opened three or four batteries on us, and made the shot rattle around us pretty lively.

" One of those shrapnel shells exploded near me and forty-eight pieces of it entered my body. My right arm was shattered and my left eye was put out. I was carried a short distance to the rear as dead, and knew nothing more until two days after.

" When I regained consciousness, I was in a wagon with a lot of dead comrades being carted to the trenches to be buried. I moaned and called the attention of the driver, who came to my assistance, pulled me up from among the dead, and gave me a drink of water. He said the first words I uttered, after he gave me the water, were: 'Did we win the battle ?'

" Then I was taken to the First Army Corps Hospital. It was a farm owned by Isaac Lightner, three miles from Gettysburg, on the Baltimore Turnpike. They laid me down beside the barn, where I waited three more days before my wounds were dressed. The surgeon let me lie there to 'finish dying,' as they said, while they attended to all the rest of the wounded. No one thought that I could live another hour. I lay on the barn floor several days, and was then taken into the house, where I stopped for a week. From there I was removed to Seminary Hospital.

" After about three weeks I was carried out of the hospital to die again, and was told by the head surgeon that I could not live six hours, but I did not do him the favor. I graduated with honors from that Seminary in about three months, and was sent to West Philadelphia Hospital, where I remained until I was able to return to my home in Augusta, Maine."

Source: Deeds of Valor, p. 157

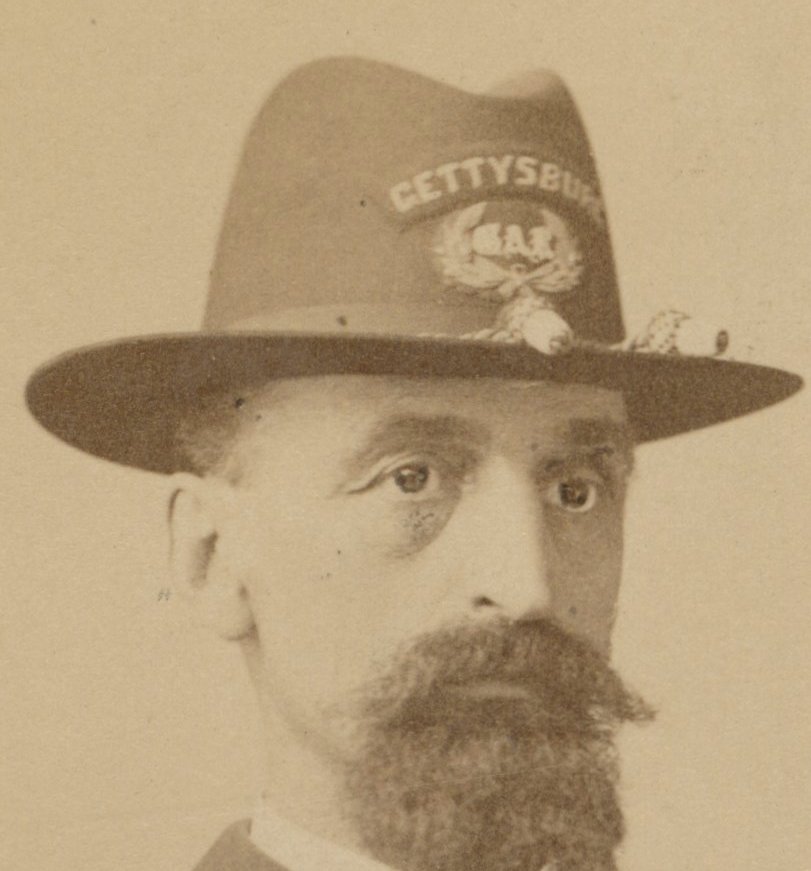

Cabinet Card size image and note the word "Gettysburg" on his hat.